Missionaries or Crusaders?

What two conferences in my city reveal about how Christians think about cultural change.

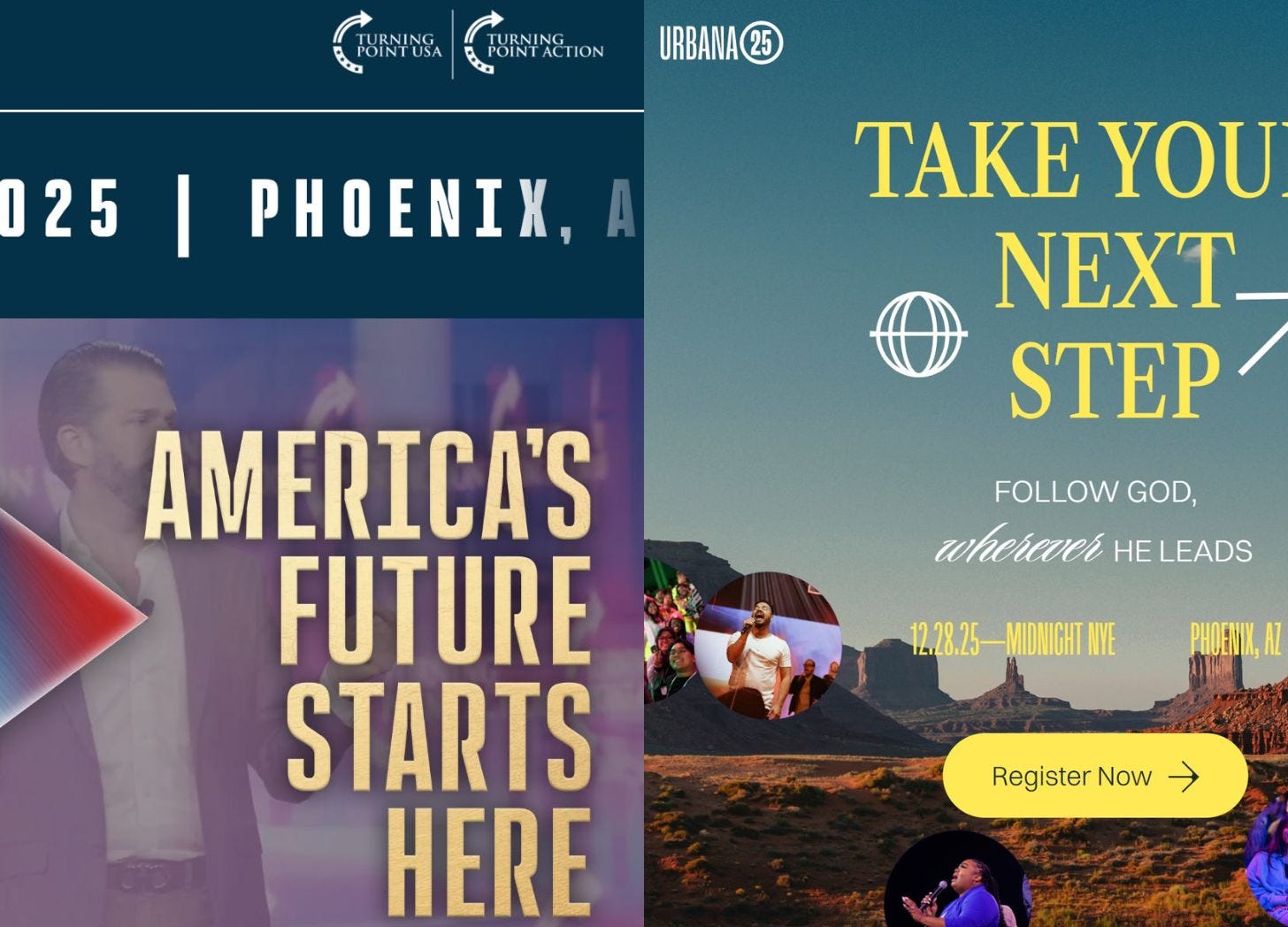

This month, the Phoenix Convention Center will host two large conferences organized by Christian groups. One describes its purpose as “bearing witness to the Kingdom.” The other calls Christians to “fight for the future of America.”

Both will quote Scripture.

Both will claim allegiance to Jesus.

Both will sing worship songs.

Both will speak about the church’s calling to impact the world.

And yet, they are animated by profoundly different visions of how the church engages and influences the cultures it inhabits.

One vision sees the church as a sent people called to enter a culture to bear witness to the Kingdom of God and to shape society from the bottom up through faithful presence, persuasion, and love.

The other organizes Christians to take political power and shape culture from the top down, trusting law, policy, and enforcement to secure change.

One vision forms Christians as missionaries.

The other forms them as crusaders.

Andrew F. Walls, a missionary and historian of world Christianity, names the difference clearly:

“The crusading mode and the missionary mode are sharply differing methods of extending the Christian faith. They grew up in the same areas in the same period; they coexisted and went on side by side. But they are totally different in concept and in spirit. The crusader may invite, but in the end, he is prepared to compel. The missionary cannot compel; the missionary can only demonstrate, explain, entreat, and leave the rest to God.”1

Walls’ distinction helps clarify what is really at stake between the two conferences in my city.

The missional posture holds the conviction that cultures are rarely transformed by “power over,2” but through embodied witness and faithful presence in a community3. It calls believers to live Jesus-shaped lives in which words, actions, and attitudes tell the same story. This kind of witness is not loud or forceful; it is visible, durable, and often costly.

History bears this out. In The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark shows that Christianity transformed Roman culture not through imperial power, but through patient, bottom-up practices: sacrificial service, dense networks of relationships, care for the sick during plagues, hospitality to the poor, and resilient communities that embodied a strange, compelling love in the face of suffering and death.

This is the way of the cross.

The cross reveals a form of power that looks weak by the world’s standards but proves durable over time. It refuses to buy into the illusion that lasting cultural renewal can be imposed from above.

The crusader imagination, on the other hand, assumes that culture must be changed from the top down. It believes the primary problem is who holds political power, and the primary solution is to take it, often framed as defense, combat, or recovery in a time of perceived cultural decline.

Missionaries do not control the environment. They do not set the rules. They do not assume cultural privilege. They practice faithfulness without guarantees that they will ‘win’. Crusaders, by contrast, are unwilling to relinquish control.

Missionaries trust bearing witness to shape culture over time.

Crusaders, by contrast, turn to compulsion and enforcement to produce change.

Top-down power can restrain behavior for a season. It cannot form virtue. It cannot produce love. It cannot create the kind of shared moral imagination that sustains a culture over generations.

If our desire is for people to know Jesus and experience the abundant life of his way, then we must ask whether our methods reflect the cross we proclaim.

Perhaps it is time for us to ask which posture is forming us right now. Will we choose the “power-under” way of the missionary, or the “power-over” way of the crusader?

Andrew F Walls, The Missionary Movement from the West : A Biography from Birth to Old Age.

James Davison Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity, esp 129-131.

Alan Kreider, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church.

The contrast btween "demonstrate, explain, entreat" versus "compel" cuts straight to the core tension here. Stark's research on early Christianity's growth is fascinating because it shows transformation without a single policy mandate or enforcement mechanism. The early church built credibility through lived witness during plague outbreaks, not through securing favorable legislation. I've seen modern organizations try to rush culture change from the top, and it almost always creates surface compliance without real internal buy-in. The missionary mindset accepts that genuine shifts in collective values take generations and require patient community presence, which is tough when the crusader approach promises faster visible "wins."

Good riff ... there's a groundswell of theological movement ... from Americanized Reformed theology to Spirit filled Anabaptist. The church in USA desperately needs this move.